Erik L. Smith and Kenneth A. Runes

Disclaimer: This section discusses general commonalities in the law only. Examples are not to be taken as specific legal advice. This source is not to be cited as legal authority.

How will I know?

People discover they are being investigated in three ways. The investigator tells them, they are tipped by a third party (generally someone the investigator has spoken to) or they guess. Guessing is unreliable (that strange car in front of the house could be anybody's), and in our experience, the investigator will likely not contact the person under investigation until the investigation is almost completed. The reason is simple: the investigator wants as much dirt as possible with which to confront you when the two (or more) of you finally chat, thus putting you off guard and making you more likely to confess your alleged crimes. The investigator is not talking to you because he or she cares about what you say as much as because it will look bad if you lacked an opportunity to respond to the allegations. It is unwise to talk to an investigator of any kind without a lawyer present.

The most likely way you will learn early that an investigation is afoot is by somebody telling you the investigator contacted them, interviewed them, left a business card, served a subpoena or the like. If you get this call at 9:00 in the morning, be on the phone with a lawyer by 9:05. This is why you should have a lawyer already lined up. Know that investigators for state agencies or law enforcement typically discourage those they interview from tipping you off, supposedly because it endangers the investigation. Should the person interviewed nevertheless contact you, that person is likely your friend. The people interviewed who do not call you are not necessarily enemies, just intimidated.

Who might be investigating me, and how will I know it?

In a criminal matter, you will be investigated by the State's Attorney, Sheriff, Police, or some other arm of law enforcement. State agencies that oversee medical and nursing licenses generally also have in-house investigators and lawyers who act as prosecutors in administrative proceedings (like when the State agency alleges that a midwife is practicing medicine or nursing without the proper license). As noted, the public servants who investigate you will not likely advise you of the investigation until they confront you, so the most likely way you will find out earlier is by word of mouth.

In a civil situation, e.g. when the midwife is accused of professional negligence, malpractice or wrongful death, any investigation before the complaint or suit is filed will likely be done by private investigators working for the plaintiff's attorney. Private Investigators (PIs) operate close to the boundaries of privacy laws, and often when they interview people they do not identify themselves or their clients. You probably will not know about the lawsuit until you are served with a complaint and summons to appear. After suit is filed, the parties engage in cooperative discovery, a process described later in this chapter.

What do they do with the results of their investigation?

When law enforcement of any stripe investigates a situation, they are trying to determine whether probable cause exists to determine that a crime has been committed, e.g. involuntary manslaughter, practicing medicine or nursing without a license, unauthorized use or distribution of prescription or controlled substances. If they believe they have unearthed enough information to charge you, they will do so, either by use of information or by grand jury (discussed in detail later). If they do not find enough information to charge, they will keep investigating or drop the matter. Law enforcement usually does not drop matters however. Like anyone, they want to find what they are looking for.

The investigator for a state agency is trying to determine whether sufficient evidence exists to show you are practicing medicine or nursing without a license, practicing in a way your license does not permit, or otherwise violating agency rules or state statutes (as interpreted by the agency, of course). See if this sounds familiar: If they do not find enough information to bring an administrative complaint, they will keep investigating or drop the matter. Law enforcement usually does not drop matters however. Like anyone, they want to find what they are looking for. They do have one other option: to deliver their findings to law enforcement (see above).

In the civil scenario, the investigator will find whatever he or she can and give the results back to the person who hired them (generally plaintiff's attorney). During the discovery phase, which comes after the complaint is filed, your attorney can legally demand the other party reveal to you the documents and information the PI gathered.

What if they come with a search warrant?

If law enforcement or a state agency comes to your door with a court-ordered search warrant, they will likely have right to search the premises described in the warrant with or without your consent. If you have an attorney, this would be an excellent time to phone him or her for advice. But (as discussed in Section IV) don't ever consent to any search of your property, office, car, etc., whether or not law enforcement has a search warrant. Be straightforward. Say, "I don't consent to this search!", "I don't agree!" or "I want to be clear that you are conducting this search without my permission!" Don't say "Well, OK," or "I guess I have no choice since you have a warrant" or anything that could be twisted to imply you consented, relented, or anything of the kind. If you don't consent, your lawyer can argue that the search was unreasonable, thus violating the Fourth Amendment and rendering everything found inadmissible as evidence. Consenting will likely compromise that argument forever.

Ask to read the search warrant and note whether the investigator(s) are looking only in the places the warrant allows. Don't leave. Once the search is underway, you have lost a fair amount of control over the situation. The way to minimize the damage is through advance planning. Law enforcement cannot find and remove property or documents not present in the place they are warranted to search. Nor can officers know what locked file cabinets and other locked areas contain unless those areas are clearly labeled, e.g. "Midwifery Records", "Unauthorized Pitocin and Oxygen", etc. In short, if you have good reason to suspect a search may occur (for instance if you are a Direct Entry Midwife), you may want to arrange for your current records and several thousand dollars of equipment not to be in your house or car. Note that if they have a broadly worded warrant, anything and anyone in the house (such as a prenatal client) may be fair game.

TERMS AND CONCEPTS

Court. "The court" means the judge or jury. "The court granted the motion" means the judge granted the motion.

Hear. Hear means "conducts the courtroom proceeding." "The court heard the arguments" means the judge conducted the proceedings and listened to the lawyers argue their points.

Parties. Parties are the people directly involved in the legal proceeding and their attorneys, not witnesses. Party means the plaintiff or defendant through their attorney. Parties can be plaintiffs, defendants, intervenors, the state, appellants, or appellees. The "plaintiff" in a lawsuit is the person bringing the suit and seeking "relief". The "defendant" is the person being sued. In a criminal case, the defendant is the person on trial. The "prosecution" is the state, represented by the prosecutor.

Equitable. Equitable relief means what is fair or just, as opposed to economic relief. The most common equitable relief is a restraining order or an injunction.

Appellate. Appellate refers to appeals. When the party losing in a case at trial appeals to a higher court, then that higher court is the "appellate" court, conducting "appellate review" of the case. The party appealing is the "appellant." The party not appealing is the "appellee."

Jurisdiction. Jurisdiction means a court's authority to hear a case based on the subject matter, where the parties live or do business, and whether the case is an appeal or being heard for the first time. Whether a case is in state or federal court, trial or appeals court, the judge's first task is to decide whether the Court has jurisdiction over the parties and the subject matter.

Acquitted. Acquitted means found not guilty.

Miranda rights. The rights read upon arrest: the "right to remain silent, to have an attorney..."

Regarding legal proceedings there are three basic types of law: criminal, civil, and administrative. Criminal law deals with crimes and their prosecution. Civil law is the law governing the relations between private persons or organizations. Administrative law is the law regarding the rules or regulations made and enforced by governmental agencies.

Criminal lawCriminal cases involve charges brought by the state under that state's criminal laws. The goal is to punish offenders for violating the criminal laws by assessing the offenders with fines, imprisonment, or probation. Thus, crimes are offenses against the state, not against individuals. The individual suffering from the crime is the "victim." Victims are witnesses. The party bringing the case to court is the "state," represented by the prosecutor. The prosecutor's party name is the "prosecution." The state may also be the "people" or the "commonwealth." Bringing a criminal charge to court and carrying it through is called "prosecuting" the defendant.

Criminal offenses are almost always written laws. They are labeled for identification, (e.g. "murder," "manslaughter") but defined by parts, called "elements," each of which the prosecution must prove to get a guilty verdict. Failure to prove just one element of the crime results in the defendant's acquittal of that criminal charge. For example, to prove "negligent homicide," the prosecution might have to prove that the defendant (1) negligently (2) caused (3) the death of another (4) by means of a dangerous weapon, material, or instrument.

Crimes fall into two general categories, misdemeanors and felonies. Misdemeanors are crimes punishable typically by fines or jail sentences of one year or less. Felonies are crimes punishable by jail sentences typically exceeding one year. States divide related offenses into degrees of severity. The higher the degree, the less "serious" the crime, and lighter the sentence. For example, involuntary manslaughter ("reckless homicide") which might be defined as (1) the death of another (2) directly caused by (3) committing another offense, might be a felony of the third degree, carrying a maximum sentence of five years imprisonment and maximum fine of $15,000.00. Voluntary manslaughter, which might be defined as a person (1) under the influence of (2) sudden (3) provoked (4) rage (5) knowingly (6) causing (7) the death of another, might be a felony of the first degree, carrying a maximum sentence of ten years imprisonment and maximum fine of $20,000.00. Negligent homicide might be a first-degree misdemeanor, carrying a maximum sentence of six months imprisonment and maximum fine of $1000.00.

If a prosecutor prosecuting a defendant for all three of these criminal offenses can prove neither the "knowingly" element of voluntary manslaughter nor the "committing another offense" element of involuntary manslaughter, then the defendant will be acquitted of those two charges, but may still be found guilty of negligent homicide, the first-degree misdemeanor--because the defendant only negligently (unintentionally) caused the death by using an instrument. If the prosecutor can prove every element of all three offenses except the "cause" element in each offense, then the defendant is acquitted of all three offenses. A midwife might be found guilty of "involuntary manslaughter" for example, if she negligently caused a newborn's death while committing unauthorized practice of medicine--because she caused the death of another while committing another offense.

The burden of proof in a criminal proceeding is "beyond a reasonable doubt," which means being firmly convinced that the defendant is guilty. (See also "Types of Crimes involving midwives")

Civil lawCivil law deals with relations between private persons or organizations. A plaintiff in a civil case sues to redress a lost personal interest, be it money, property, or liberty. Licenses and certificates are property. Relief might include the enforcement of a contract, compensation from the defendant for the plaintiff's physical or economic harm, or a court order telling the defendant to do or not do something (e.g. "injunction"). Thus, in a civil proceeding, the question for the court is not guilt or innocence, but liability for the defendant's injury, or whether to grant some equitable ("fair") relief where money is not the object.

In civil proceedings, the standard of proof is most often "preponderance of the evidence" (a.k.a. "the greater weight" or 50.1%). But in some cases where fraud or criminal conduct is alleged in a civil court or a license is at stake, a "clear and convincing" standard may apply. There is no presumption for or against either party, though the plaintiff bears the burden of proving the defendant‘s liability. A person can be sued civilly after being tried criminally for the same behavior, whether acquitted or convicted in the previous criminal trial. For example, a midwife could be tried for wrongful death (a civil claim) after being acquitted of manslaughter (a criminal charge). (See "Double Jeopardy")

One can never be jailed for liability in a civil lawsuit, though a party in a civil case may be jailed for contempt of court. Contempt of court means intentionally interfering with the administration of justice (e.g. not following a court order).

Civil cases involve six basic types of disputes:

A civil case may involve more than one of these controversy types. For instance, a lawsuit against a midwife for damages she caused to a newborn (a tort) may feature an immediate order preventing the midwife from practicing during the lawsuit (an injunction), and a claim by the midwife that a relevant law or regulation restricting her is invalid or unconstitutional (declaratory action and perhaps civil rights action). The midwife may even have had a contract with the client, which might be relevant to liability.

(1) Lawsuits for damages (torts)

The torts most likely to be brought against midwives (under normal practice) are claims for negligence. Negligence includes claims of wrongful death, malpractice (professional negligence), and gross negligence. Negligence is the (1) breach of a duty (2) directly causing (3) damages to the plaintiff. A licensed or certified midwife owes a client a fiduciary (professional) duty, that is, a duty of a special trust and care. To show she breached that duty--in a legal state-- the defendant usually must get testimony from other qualified midwives that the midwife's actions fell below the established standard of care for midwives in the midwifery community.

Wrongful death is simply negligence where the damage is death. Negligence becomes gross negligence if the defendant "recklessly" breached her duty of care. An unlicensed midwife might be prosecuted criminally for manslaughter or unauthorized practice, and sued civilly for negligence or wrongful death. The state would prosecute the crime. The client would prosecute the civil case.

(2) Requests for court orders (injunctions)

The most common court order one seeks in a civil case involving midwifery is a type of restraining order called an "injunction." An injunction seeks to stop an individual from performing some action. For example, a state board might seek an injunction ordering an unlicensed midwife from "practicing nurse-midwifery without a license." In turn, a midwife may seek an injunction ordering a state board to refrain from enforcing a law or regulation. Less commonly, injunctions can order a person or entity to perform some action. In either case, the person against whom the injunction is ordered is "enjoined." In most jurisdictions, the party seeking the injunction must show entitlement to the relief by clear and convincing evidence.

(3) Civil rights actions

Civil rights actions are lawsuits brought against a governmental authority, or agent acting under that authority, for harming the plaintiff by violating the U.S. Constitution or other federal law. The claim is brought under a specific federal statute, 42 U.S.C. 1983, enabling the plaintiff to sue in federal court. For example, an aspiring midwife may have standing to bring a civil rights claim where the state licensure requirements are so unreasonable that they discriminate against her and her clients. States have civil rights statutes also, letting plaintiffs sue in state court when the governmental authority or agent under that authority has violated plaintiffs' constitutional rights (see Interaction between criminal, civil, and administrative law). Civil rights actions often involve declaratory actions. There are many cases in the federal courts of Appeals, not to mention the Eleventh Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which greatly restrict the ability to sue state and local governments for monetary damages. There are also legal doctrines that usually require that state and local governments be sued in State Courts and not Federal Courts.

(4) Declaratory actions

A declaratory action asks the court to declare the plaintiff's right or legal status under a law, contract, or other instrument. This can include a constitutional clause or amendment. For example, a midwife may seek a judgment declaring that a licensing regulation or medical practice statute is unconstitutional. Declaratory actions usually come with requests for injunctions to prevent the losing party from enforcing the law or regulation.

(5) Disputes over contracts or other agreements

A midwife practicing legally may have a contract with the client. Thus, a civil case might include a civil action to enforce the contract (e.g. about payment or liability clauses, etc). An action involving an insurance policy could be a contract dispute. Note that the same contract that strengthens a claim in civil court may create evidence useable in criminal court.

(6) Appeals from administrative decisions

A separate administrative tribunal hears an administrative case. Appeals from cases heard administratively are brought in a general county civil court. (See "Interaction between criminal, civil, and administrative law" and "Types of Courts")

Administrative lawAdministrative law is that law dealing with the various organs of the state government that let commissions or boards regulate professions. The legislature creates a commission or board, then passes general laws about how the board or commission will conduct its activities. A state administrative agency might be called something like the "Department of Business and Professional Regulation" or "Board of Medical Examiners." The legislature gives these boards or commissions authority to make its own rules and regulations and enforce their compliance. The rules and regulations are valid provided they do not oppose, modify, overly extend, or overly restrict the legislature's original laws. In enforcing their rules and regulations, administrative agencies can investigate suspected non-compliance and hold hearings to decide relevant controversies. Upon finding a violation, administrative agencies have several possible remedies. They can suspend, revoke, or cancel licenses or certificates, pursue criminal charges, seek court orders, or issue "cease and desist" orders to non-licensed offenders of the rules and regulations.

States recognize three general types of laws: codified, court rules, and case law. (The United States government is a "State" in this context).

Codified law

Codified laws are statutes and administrative rules and regulations.

Statutes

Statutes are the general, written laws a state enacts, collectively called "statutory law." Statutes are found in "state codes" (e.g. Ohio Revised Code, South Dakota Codified Laws). State codes are divided into chapters, each referring to a category of law, such as criminal, insurance, family, civil remedies, etc. The chapters are considered individual codes. An entire state code may contain as many as fifty separate chapters. State codes are often annotated, meaning they list the statutes as well as relevant court cases, articles, and administrative code sections. Codes can put several statutes speaking to one topic into a group, called an "Act" (e.g. the "Medical Practice Act"). When several statutes interrelate on one legal topic, but do not constitute an Act, legal professionals call them a "statutory scheme."

Administrative code

A state's administrative code contains the regulations governing the state's administrative agencies. The agency regulations cannot go beyond the authority granted the agency by statute. The state legislature gives the administrative agency authority to decide its own procedures and make its own regulations. As long as the rules and regulations do not contradict, go beyond, overly restrict, or modify the general state statutes, they are valid. For example, a statute might say that a licensed physician must supervise a midwife. The administrative code may then validly pass a rule or regulation that says the physician must document the supervision in a certain way. But an agency regulation requiring the supervising physician to be licensed in that state may be an invalid exercise of the authority delegated to it by the legislature because the statute did not say the supervising physician had to be licensed instate.

Court rules

Court rules are the rules of evidence and procedure courts or administrative agencies follow in conducting their actual proceedings. Separate rules exist for criminal procedure, criminal evidence, appellate procedure, administrative procedure, and Supreme Court procedure. Some of the separate court's rules may duplicate each other or differ only slightly. But they are still different rules.

Case law

Case law is the decisions made by Appellate courts and published as "opinions." Because Appellate courts interpret and apply the written laws to factual situations, case law interprets codified law. For example, a state medical practice act may prohibit "treating abnormal physical conditions." A midwife convicted of unauthorized practice of medicine may argue on appeal that she did not treat an "abnormal" condition. The appellate court will then determine whether the statute in the medical practice act really meant to include pregnancy in its concept of abnormal. The appellate court then renders a written opinion featuring its definitive answer, called a "holding." The holding might read: "Pregnancy is not an abnormal condition as referred to under R.C. 3200.09 of the medical practice act, thus we reverse the conviction in the trial court." The court will then justify its reasoning for that conclusion with a several page opinion, describing the facts and other appellate holdings it relied on as authority. The holding becomes precedent that other courts in the district must follow. On occasion, appellate courts overrule their precedents. This is rare. But the Supreme Court can reverse any appellate opinion--and even its own previous opinion.

The decisions of state trial courts are rarely published. But state appellate and Supreme Court decisions are published in case law books called "Reporters." This lets other judges cite those cases as authority for their decisions. Federal district court opinions are published in a reporter called the "Federal Supplement" and are "persuasive authority," meaning other courts may follow that case's reasoning if they so choose. Federal appellate opinions are published in the "Federal Reporter." U.S. Supreme Court opinions are published officially in the United States Reports. Being appellate opinions, they are "primary" authority, meaning trial courts in their jurisdiction must follow them.

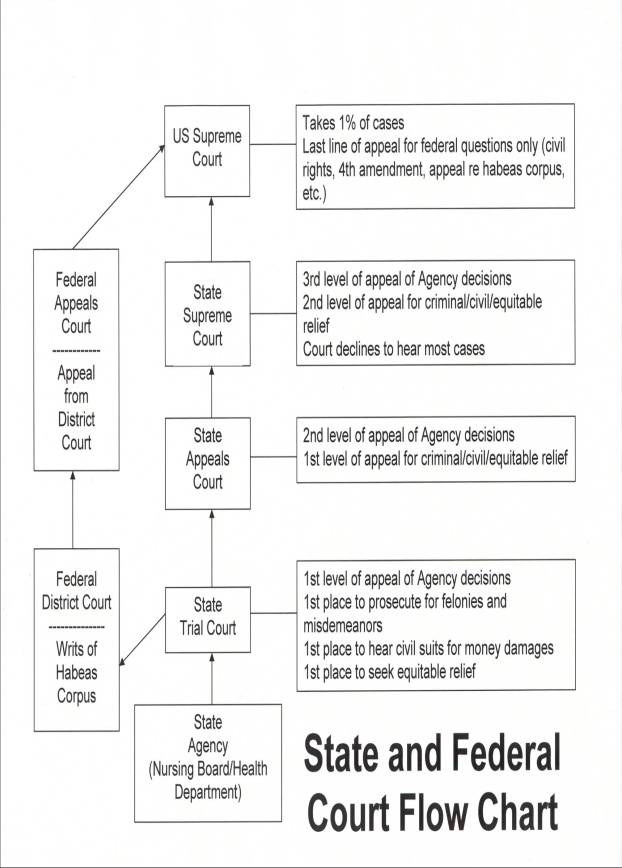

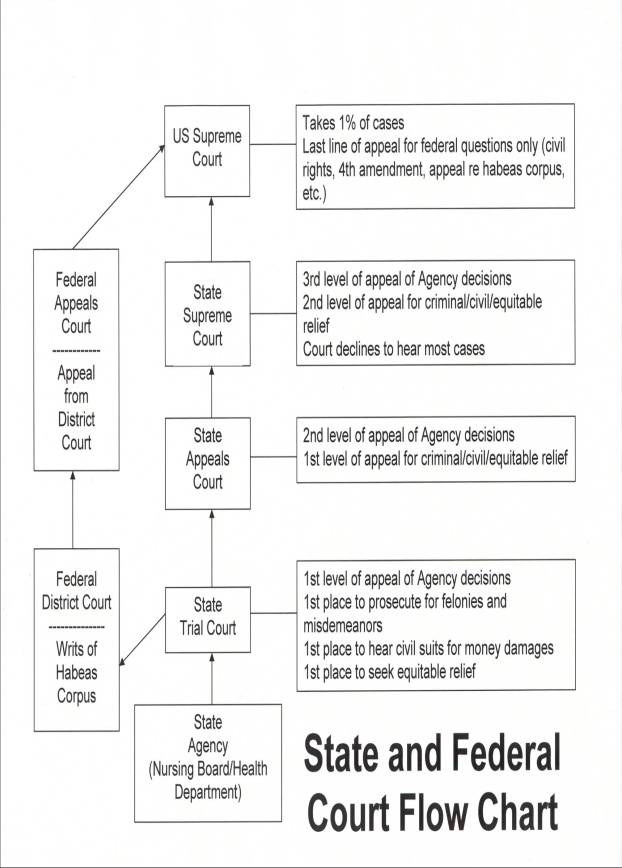

Jurisdiction/Federal & State

State and federal cases have original jurisdiction over cases involving their own laws. However, federal courts have jurisdiction to decide state cases in two situations: (1) the parties in a civil suit reside in different states and the amount in controversy is at least $75,000 ("diversity jurisdiction") and (2) the state law in question violates a federal law or constitutional right. Suing for the latter in the midwifery context would be a "civil rights action" (see Civil rights actions) The plaintiff could sue in the state's county civil court or in federal district court.

Midwifery laws are state laws. Thus, unless a party brings a civil rights claim, or the parties in a civil case reside in different states, all midwifery cases, criminal, civil, and administrative will be filed first in a state court. Diversity jurisdiction does not apply in criminal cases. State criminal cases are filed in the court of the county where the alleged crime occurred.

A case filed in state court can later be heard in federal court under certain circumstances. One is where a party has exhausted its appeals in the state courts and then convinces the U.S. Supreme Court to review the case. Another instance occurs where a plaintiff brings an action in state court that it could have brought in federal court (e.g. civil rights action or diversity case). A party can then "remove" the case to federal court. However, no case can ever be tried and fully resolved twice anywhere, either in the same court or a different court. This violates the doctrine of res judicata (Latin for "a matter settled by judgment"), which is the civil version of double jeopardy (the right not to be tried again after being acquitted). (See, "Double Jeopardy")

State and federal courts can also overlap, so to speak, where a state criminal defendant asks a federal court to order her released from jail or granted a new trial because the state conviction or trial violated the U.S. Constitution. The defense petitions the federal court, asking it to order the prisoner released on those grounds. The remedy is called a petition for writ of habeas corpus. Because states have individual constitutions, states allow habeas corpus petitions to be brought in their own courts also. State constitutions are valid provided they do not contradict the U.S. Constitution. Habeas Corpus petitions are usually unsuccessful.

Court Levels (Trial, Appellate, Supreme)

State and federal courts have three levels: trial, appellate, and supreme.

Trial courts

Civil lawsuits and criminal prosecutions start in the trial court, which is where the trial occurs. It is the only court level at which a jury can be used because it is the only court that determines facts. In reaching a verdict (decision) the trial court hears and assesses the evidence. It then finds facts and makes legal conclusions in reaching its verdict. In jury cases, the judge makes any legal conclusions and instructs the jury about what questions to consider in making their factual findings. Thus, juries are the "triers of fact." Where the parties choose not to use a jury, the judge is the trier of fact and decides the entire case. States have their own particular names for their trial courts, for example, "district" court (in Texas), "common pleas" court (in Ohio). Trial court decisions set no formal legal precedent. No trial court need adhere to any other trial court's theory or decision in a different case.

Appellate Courts

Appellate courts are "review" courts. They are the courts to which the loser of a case in the trial court appeals. Appellate courts never "retry" cases or accept or hear new evidence. Their sole task is to review whether the trial court erred legally or procedurally. Appellate decisions set legal precedent that trial courts in the same geographical area ("district") must follow. Appellate courts may not substitute their judgment for that of the trial court by reviewing the case to see if it would have reached a different conclusion had it been the judge or jury. Nor will appellate courts normally consider issues the parties did not present at the trial. Parties in a case have the right, by statute, to file an appeal. But an appellate court may dismiss a frivolous or procedurally flawed appeal.

Appellate courts decide cases on the written legal arguments the lawyers submit ("briefs") and the oral arguments the lawyers make before the justices. The parties and the justices have access to the record from the trial court. The number of justices hearing an appeal varies from state to state, but a typical number is three or five. If the appellate court decides, by majority vote of the justices, that the trial court did not err, then it "affirms" (upholds) the trial court decision. If the trial court did err, then the appellate court either agrees completely with the person appealing and "reverses" the trial court decision, or "remands" the case back to the trial court so the trial court can correct its error, usually by having a new trial. If the Appellate Court issues a written opinion, it becomes precedent for trial courts in that district to follow ("case law"). In deciding a case, a trial court can consider an opinion from an appellate court outside its district if no factually similar appellate opinion exists in its own district.

Supreme Courts

Supreme courts are also review courts but, unlike the lower appellate courts, they need not review all cases submitted to them. In fact, supreme courts, both state and federal (U.S. Supreme Court), accept only a small percentage, usually less than five percent, of cases submitted to them. Because supreme courts are courts of last resort, they will review cases only under one or more of the following criteria: (a) the Appellate Court refused to follow previous supreme court rulings; (b) the various appellate courts in the state or country have reached conflicting conclusions on that same type of case, ("conflict between the circuits") or (c) the case otherwise presents an issue of immediate and significant state or national importance. Supreme courts can deny petitions for review for no stated reason at all. Should a Supreme Court decline to review the case, the case is over and the appellate decision stands. If the Supreme Court accepts a case for review, it issues an order telling the Appellate Court to transfer the record in the case to the Supreme Court ("writ of certiorari"). The Supreme Court will proceed as an appellate court, with briefs submitted by the lawyers followed by one-time oral arguments from both sides. The Supreme Court's ultimate decision must be followed in its entire jurisdiction, which means the entire state or, in the case of the U.S. Supreme Court, the country. The U.S. Supreme Court has nine justices. All federal court justices and judges, at all levels, are appointed by nomination and serve for life unless they resign or retire. States assign justices to their supreme courts by nomination or election.

Levels and Divisions of Trial Courts

(a) State

States have different levels of trial courts. These are, from lowest to highest: Justice of the Peace or Mayor's Courts, Municipal Courts, and County Courts.

- Justice of the Peace or Mayor's courts

Justice of the Peace/Mayors Courts are often presided over by a justice of the peace or an elected official, such as the mayor, or by someone delegated by that elected official. These courts deal typically with very local issues such as city or township ordinance violations, marriages, and minor civil matters.

- Municipal courts

Municipal courts generally hear civil cases where the damage amounts sought are relatively small, and routine misdemeanor criminal cases. Municipal courts might have a separate small claims division for certain minimum money amount civil cases, for example, less than $3000.00. A typical jurisdictional limit for a municipal court in a civil case might be $15,000.00. Geographically, municipal courts have very local jurisdiction, (e.g. the city).

- County courts

The county courts are the state's main trial courts. They hear civil cases where the money amounts sought are beyond the limit of the municipal courts, criminal cases beyond routine misdemeanors, and equitable cases like probate, family law matters, and requests for injunctions, etc. Their geographical jurisdiction is usually limited to the county and possibly the few small surrounding counties. The county courts have separate court divisions for different subject matter, such as criminal, general civil, probate (wills and estates), domestic relations (divorces and child custody disputes), and Juvenile (crimes involving minors, paternity suits, and neglected child cases, etc). Most midwifery state cases--non-administrative--will start in the county general civil or criminal court. The general civil court will be the first appellate court for review of an administrative decision.

(b) Federal court structure

Federal court structure is much the same as the state structure. There is the trial court, called the "district" court, the Appellate Courts, called the "circuit" courts, and the Supreme Court. The federal system has separate trial courts for bankruptcy, military appeals, customs and patents, and tax cases. These courts will not likely hear midwifery cases. Rather, the general district court will hear federal cases involving midwifery (see Civil Rights Actions, Section C(3)). The federal district court hears cases arising under federal laws or the U.S. Constitution; admiralty, maritime, and prize cases (high seas); appeals from federal administrative agency decisions, and civil cases between citizens of different states where the amount in controversy is at least $75,000.00.

Stages of Prosecution

Criminal cases consist of the following twelve general stages:

1. Arrest

Police may make an arrest with or without a warrant.

- Warrantless arrest

A law enforcement officer may arrest a person without a warrant if he has "probable cause" to believe the person has committed a felony. A police officer's own observation and information he receives from reasonably trustworthy persons can satisfy probable cause to arrest. Later acquittal or dismissal, in itself, does not mean the arrest was wrongful.

States may differ on the restrictions regarding arrests for misdemeanors. Some states require that, unless the officer observes an individual committing a certain misdemeanor, the officer issues the suspect a citation, which then obligates the accused to appear in court.

- Warranted arrest

A warrant is a written authorization from the Court to arrest a certain person. Arrest warrants usually come after a citizen has executed a sworn statement with the police or prosecutor. The clerk of court may then issue the warrant for arrest.

2. Initial appearance

An officer making an arrest must, within a short time, take the defendant before the court and file a complaint. This is the "initial appearance." There, the defendant and her attorney read the complaint. The court informs the defendant of the charges, her right to refuse to make a statement, and to have a preliminary hearing (unless the grand jury already returned an indictment (see Section F(1)(4)), and to a trial by jury. The court sets bail and, if the charge is a misdemeanor, may ask how the defendant pleads. In many states, the court may not let a defendant enter a plea at the initial appearance or the preliminary hearing if the charged offense is a felony. The initial appearance is brief and the defendant may be one of many defendants having their initial appearance in that courtroom that day.

Common types of bail are personal recognizance, a bail bond requiring a percentage deposit, a surety bond secured by real estate or securities, or a cash deposit. The bail will involve conditions, such as promising to appear at trial and other hearings. Other conditions may include restrictions on travel, residence, or association; house arrest, restricted contact with the victim and witnesses, or a requirement to attend drug treatment. If you cannot post bail, you still have the right to speak to an attorney. States vary in the number and length, etc., of phone calls you can make in finding an attorney. It helps greatly if you already have a relationship with an attorney. The next phase is the preliminary hearing.

3. Preliminary hearing

The preliminary hearing is a "probable cause" hearing, meaning the court observes the evidence to see if it is enough to warrant prosecution. Thus, the prosecution need not present all of its evidence, but just enough to satisfy probable cause. The hearing is conducted in municipal or county court. The prosecutor may make an opening statement, present evidence, and call witnesses. The defense attorney may cross-examine the witnesses and present her own witnesses. If probable cause does not exist, the judge releases the defendant. If probable cause exists and the offense is a misdemeanor, the judge will order a complaint filed, and set the case for trial or refer it to the appropriate court. If the offense is a felony, and the judge rules that probable cause exists, the court will "bind the defendant over" to the grand jury.

4. Grand jury

The grand jury is seven to fifteen people summoned randomly from the community to decide if probable cause exists to prosecute the defendant. The jurors hear the prosecutor privately and evaluate his evidence. If they conclude by a certain majority vote that the evidence established probable cause that the defendant committed the crime, then they return a written formal statement charging the defendant with the crime. That statement is the "indictment."

Jury members can compel witnesses to attend the hearing and to produce documents. For security reasons, grand jury proceedings are secret. Neither the defendant nor her attorney has right to be present or know what went on. The prosecutor may call the defendant to testify, or consent to have the defendant testify. But neither the defendant nor witnesses have right to an attorney being present or to question witnesses. The defendant may assert her Fifth Amendment rights against self-incrimination, but no one need advise her of her constitutional rights.

The defendant's attorney may challenge an indictment on the ground that the jury was improperly selected (e.g. non-randomly) or that the defendant was prejudiced by delay or by unauthorized persons being present. If the jury decides probable cause to prosecute does not exist, it issues a "no bill," and the defendant is not brought to trial. Whether the grand jury finds probable cause does not depend on whether your client supports you. Remember, the state--not the alleged victim--is the party in interest in criminal prosecutions.

5. Information

Regarding certain felonies, some states let prosecution proceed by "information." An information is a written criminal charge that the prosecutor drafts and files with the court. It describes the charge and identifies the supporting factual allegations. Many states allow prosecution by information regularly regarding misdemeanors.

If the defense feels the information is too vague, it can make a request in writing to the prosecutor for more specifics. This is a "bill of particulars." The bill is especially necessary where the defendant has an alibi, yet the information does not specify the date and time of the offense that would support the alibi. Many states require a defendant file a notice of alibi before the trial starts lest she waive arguing an alibi at trial.

An indictment or information can charge multiple offenses, or charge separate degrees of the offense provided the offenses are similar and occurred at the same general time. For example an act of midwifery resulting in a death might justify charges brought for voluntary manslaughter, involuntary manslaughter, negligent homicide, drug possession, drug purchasing, unauthorized practice of medicine, nursing, or midwifery. Similarly, several defendants involved in the same occurrence may be tried in the same case. If the jury returns an indictment, or if the defendant agrees to proceed via an information, the defendant is arraigned.

6. Arraignment

Here, the court informs the defendant of the charges against her and of her constitutional rights, and asks how she pleads.

- Pleas

A defendant can plead not guilty, guilty, or no contest (also called "nolo contendre.") Not guilty means the defendant denies the charge and requires the prosecutor prove guilt beyond reasonable doubt. Guilty means a complete admission of guilt. No contest means the defendant does not admit guilt, but admits the facts alleged in the indictment, complaint, or information. The court has discretion as to whether to accept a no contest plea. The benefit of a no contest plea is that it cannot be used against the defendant to show liability in a later civil case. But the defendant is still considered convicted. The prosecutor's failure to honor the plea is unprofessional conduct, for which he can be disciplined.

After entering a guilty or no contest plea, the court asks the defendant questions to decide whether she understood her constitutional rights and made the plea knowingly and voluntarily. If so, the court proceeds to sentencing. If not, the court can refuse to accept the plea.

- Plea bargaining

A plea bargain is an agreement between the defendant and the prosecutor that the defendant will avoid trial by pleading guilty to a lesser offense than the one with which she was charged. The bargain may include a condition requiring the defendant to testify against another accused. The court does not participate in the bargaining, but it can reject the proposed plea bargain if it feels it would not serve public interest and justice. During the bargaining, the prosecutor can threaten to add more serious offenses to the charges should the defendant refuse to plead guilty. This is not coercion.

A defendant can withdraw a plea after sentencing if a manifest injustice occurred, such as the prosecutor breached the plea agreement, or the defendant misunderstood plea bargain terms.

- Affirmative defensesIn addition to pleading not guilty, a defendant may plead affirmative defenses. An affirmative defense is an excuse or justification for the alleged criminal act. For example, a defendant may allege entrapment (the police encouraged the crime), statute of limitations (the state missed the deadline for bringing the charge), mistake of fact (honestly misperceiving a situation), or necessity (e.g. self-defense). Other available, non-affirmative defenses include alibi, immunity, and double jeopardy. (See "Double Jeopardy" Section)

7. Discovery

Discovery is obtaining evidence from the other side before trial upon written request. The defendant may request the prosecutor turn over written or recorded statements, the defendant's prior criminal record, allow access to papers, books, documents, photos, buildings, and places, etc., identify witnesses, and reveal all evidence favorable to the defendant. The prosecutor may request the same from the defendant, but only if the defendant has requested that discovery first. Information falling under the attorney/client privilege is not discoverable.

8. Pre-trial motions

Before trial, the attorneys may make various pre-trial "motions." Motions are requests to the court asking it to make a ruling or order. Two common motions defense attorneys file are motions to "suppress" and motions "in limine" (pronounced ‘limony').

- Motion to suppress

A motion to suppress asks the trial court to exclude certain evidence because the police or prosecutor obtained it illegally--by violating a constitutional right, statute, rule, or regulation. Suppress motions can be crucial for two reasons: (1) the prosecutor's case may depend on the evidence the defense seeks to exclude, (2) the defendant may need to file a motion to suppress to preserve the right to argue the illegality of the evidence at trial or on appeal. Examples of such crucial evidence might be a defendant's confession, admission, or statement.

Courts typically grant motions to suppress when admissions, statements, or confessions were obtained through fear, coercion, physical abuse, or threats; or in violation of defendants' fourth amendment right to be free of unlawful searches and seizures (e.g. lack of probable cause for the search), fifth amendment right against self-incrimination (e.g. no Miranda rights given), or sixth amendment right to confer with a lawyer (E.g. eavesdropping on a private attorney/client conversation). If the trial court denies the motion to suppress the evidence and then finds the defendant guilty, but the appellate court holds that the motion to suppress should have been granted, the Appellate Court still will reverse the conviction only if that illegal evidence contributed to the conviction.

- Motion in limine

A motion in limine is a written motion asking the court to protect the defendant or the state from inquiring into certain "areas" that, by the very question asked, or statement made, may prejudice the jury. For example, the defense may not want the prosecutor to make statements or inquire about a previous, unrelated investigation of the defendant midwife. If the court grants the motion in limine, the attorneys cannot make statements or ask questions relating to that "area of inquiry" until the court determines, from the total circumstances of the case, whether it should allow the evidence.

9. Jury selection/Voir dire

Jury selection begins with voir dire. Voir dire is a preliminary oral examination of the potential jurors. A state may require a certain number of jurors to sit in a case. But the court summons more than that amount to form a jury pool from which the pre-requisite number of jurors, and perhaps a couple of alternates, are selected. The voir dire examination determines if any of the prospective jurors are unqualified to serve for some legal reason, or might be biased. The prospective jurors answer the lawyers' questions under oath, individually or as a group, to eliminate those persons for cause or on peremptory challenge.

- Cause

Cause means eliminating a prospective juror for a valid legal reason. Valid legal reasons include convictions for certain crimes; served as a juror in a civil or criminal case regarding the same act; or is related to the victim, the complainant, the defendant, or one of the attorneys.

- Peremptory challenges

Prospective jurors may be eliminated without cause through "peremptory challenges." Peremptory challenges let the defense or prosecution dismiss a juror for any reason except race, ethnicity, or gender. States vary as to how many peremptory challenges the parties get. But the prosecutor and the defendant get the same number.

A strike for cause might be justified if, in questioning, a prospective juror states, "We need to teach midwives a lesson." But a defense lawyer may need to use a peremptory challenge if she wants to eliminate anyone with a medical or nursing degree.

10. Trial

The trial, in the traditional courtroom sense, proceeds in the following six stages:

(1) Opening statement

In the opening statements, the prosecutor and defense attorney summarize the issues and the evidence each will present, the prosecutor going first. The defense may make her opening statement either right after the prosecutor, or after the state has presented its evidence. After the opening statements, the state presents its evidence by calling its witnesses.

(2) State's evidence

The state calls it witnesses in order. Courts recognize two main types of witnesses: fact and expert. Fact witnesses are those who know facts relevant to the case. Expert witnesses are those who have specialized knowledge they will use to give professional opinions about what certain evidence means. Thus, experts are not witnesses to the alleged events, but offer professional opinions based on the evidence they are asked to review. A coroner or pathologist asked to give an opinion about the cause of a newborn's death is an expert witness. But a doctor who never treated anyone in the case but who was watering his lawn when the defendant walked by and said, "I delivered a stillborn last night," is a fact witness. Expert witnesses are paid for their time on the case. Fact witness are not paid, but may be reimbursed for travel.

The prosecutor elicits the witnesses' testimony through questions. This is "direct examination." When the prosecutor is done with direct examination, he "passes" the witness. The defense attorney may then question the witness to impeach (refute) the testimony or clarify the truth. This is "cross-examination." After the defense attorney passes the witness, the prosecutor may ask the witness follow-up or rebuttal-type questions to repair the damage done by the defense attorney. This is "redirect examination." The procedure continues for each witness.

The procedure is the same regarding expert witnesses, except that before direct-examination, the prosecutor must establish through questioning that the witness is qualified to testify on the subject matter. Experts might include doctors, psychologists, other midwives, or coroners, etc.

At the close of the state's evidence, the defense may make a "motion for acquittal" (to find the defendant not guilty). The court will grant the motion if it believes reasonable minds could only acquit. Should the court deny the motion, which it usually does, the defense puts on its evidence. The judge cannot find the defendant guilty at this point, or at any point if the trial is by jury.

(3) Defendant's evidence

The procedure for the defendant's evidence is the same as that for the state's evidence, except that the defense attorney is the direct and re-direct examiner, and the prosecutor is the cross-examiner. The defense may call its own expert witnesses, whereupon the defense attorney must qualify them. When the defense rests (finishes with all of its witnesses) the prosecutor may present rebuttal evidence. Remember, the defendant cannot be forced to testify, she can only do so voluntarily. If the defendant volunteers to testify, then she waives her Fifth Amendment right to avoid self-incrimination and she may be cross-examined by the state.

(4) State's rebuttal evidence

Rebuttal evidence is arguments or facts intended to contradict the evidence the opposing party presented. Here, the state may call witnesses, but the prosecutor's evidence is usually limited to contradicting what the defendant brought up. The prosecutor cannot raise new facts about which the defense had no knowledge. In some states, the defendant is allowed sur-rebuttal. The defense may cross-examine. After the rebuttal evidence, the attorneys make their closing arguments.

(5) Closing arguments

The closing argument lets the attorneys assist the jury in analyzing, evaluating, and applying the evidence. Nothing more. The attorneys must limit their remarks to the evidence presented. No new evidence is allowed. The prosecutor goes first, then the defense attorney, then the prosecutor concludes. The defense attorney asks for acquittal. The prosecutor asks for a guilty verdict. Both sides can ask the jury to use its own reasoning.

After the closing arguments, the judge instructs the jury on the law of the case. The judge must define reasonable doubt for the jury and tell them what questions to answer to find reasonable doubt on each element of the offense. Then the jury retires to the jury room and deliberates.

(6) Jury deliberation/verdict

After an indeterminate time, the jury will return with its verdict, guilty or not guilty. If a jury is deadlocked after a substantial time, the judge may declare a mistrial. The defendant can be tried again in a separate proceeding. If the jury decides not guilty, the defendant is released. The prosecutor cannot appeal the verdict. If the jury finds the defendant guilty, the court enters the verdict into the record and sets a time for sentencing. A jury's verdict must be unanimous.

11. Post-verdict remedies

A defendant found guilty may still have remedies in the trial court. Two common remedies are "motion to arrest judgment" and "motion for new trial."

A motion to arrest judgment argues that the trial court lacked jurisdiction, or that the indictment, information, or complaint was fatally flawed, for example, did not charge an offense that state law recognized. Succeeding on the motion renders the indictment, information, or complaint void. The defendant is released, but the prosecutor can file new charges and start over.

A motion for new trial argues that the trial itself was flawed and needs to be redone. Valid grounds may include: irregularity in the proceedings, surprise, insufficient evidence, legal error, and that new, previously undiscoverable evidence has emerged. The particular flaw must have been significant enough to have prejudiced the defendant or denied her a fair trial, and be likely to change the result. If the judge denies all post-verdict motions, which judges usually do, the defendant's remedy is to appeal.

- Appeal

The defendant has a right to appeal a guilty verdict. Prosecutors can appeal granted motions, indictments, and sentences after guilty pleas, post conviction relief, and most other court decisions, except the final verdict.

The reasons for which appellate courts reverse or remand cases include: obvious or "plain" error in procedure or in the application of law, erroneously giving or omitting a jury instruction, insufficient evidence, ineffectiveness of counsel, abuse of discretion (arbitrarily or capriciously including, excluding, or considering evidence), and constitutional violations. Except for plain error, the defense must raise all of these issues in the trial court to preserve her right to raise them on appeal. Even if the appellate court finds these errors to have occurred, it will not reverse or remand the case unless the trial court's error likely contributed to the defendant's conviction. In some states, the defendant can appeal a conviction based on a plea bargain. The grounds can be that the sentencing was unfair, the defendant did not make an informed decision, or the defendant received ineffective assistance of counsel.

12. Post-conviction relief

Post-conviction relief generally refers to remedies the convicted has after she has used all of her appeals. A petition for post-conviction relief asks the court to vacate (remove) or correct a conviction or sentence. The usual grounds for the petition are that new, significant evidence has been discovered that will likely exonerate the convict. If the court denies the petition, the defense may appeal. If the court grants the petition, the court may either vacate the conviction, re-sentence the convicted, or grant a new trial.

Criminal offenses for which midwives have been prosecuted include unauthorized practice of medicine, nursing, and midwifery; drug possession, and manslaughter. Midwives have also been found in contempt of court for violating previous injunctions sought by administrative agencies and for refusing to testify according to plea agreements. Theoretically, midwives could, during normal practice, depending on the state, risk prosecution for negligent homicide.

Unauthorized practice offenses occur where a person practices the particular profession without license to do so or, if licensed, exceeds the limits of the license. For example, if a state allows only nurse-midwifery and requires all births occur in hospitals, then a direct-entry midwife attending a homebirth may be charged with unauthorized practice of midwifery, nursing, or medicine. Alternatively, if a state allows direct-entry midwifery and homebirths, but only lets doctors prescribe drugs, then a direct-entry midwife who prescribes drugs for a client exceeds the limit of her license and commits unauthorized practice of medicine or drug offenses. She may be criminally charged, have her licensed revoked, or be sued civilly for malpractice if she caused injury to the client or newborn (See "Election of remedies").

Contempt of court essentially means violating a court order. If the administrative agency got an injunction against the midwife ordering her not to practice nursing without a license and the midwife violated that order, she could be charged with contempt of court. A midwife could also be in contempt of court for refusing to answer a grand jury's investigative questions according to a plea agreement. For example, the prosecutor let the midwife plead guilty to a minor criminal offense (e.g. misdemeanor drug possession) in return for testifying against another midwife. Should the midwife refuse to testify, the court could order the midwife jailed until she agreed to testify. Always know the exact terms and implications of the plea agreement. The above are just two examples of facts that might lead to a contempt of court conviction.

Stages in litigation

The demand letter

A civil action officially starts when the plaintiff files a "complaint" in the court. But lawsuits for damages (torts), and some other civil controversies, informally start before that via a "demand letter" from the prospective plaintiff to the prospective defendant. The plaintiff's attorney writes to the defendant, stating that the plaintiff has been injured. The letter details why, under the facts of the case and the law, the defendant is liable for the plaintiff's injury. The would-be plaintiff closes the letter with a demand for an amount the defendant should pay the plaintiff to avoid a lawsuit. The defendant can pay the amount, offer a lesser amount, or refuse to settle and let the plaintiff file the complaint. The vast majority of torts are settled before reaching trial. Many are settled without filing a complaint.

If you receive a demand letter you should get an attorney. Once you hire one, and that attorney mails a letter of representation to the plaintiff's attorney, or responds to the demand letter, all correspondence will occur between the attorneys. An attorney should not correspond with an opposing attorney's client directly if he knows she has a lawyer. This goes both ways. The plaintiff's attorney should never call you, and you should never call the plaintiff's attorney. If the plaintiff's attorney contacts you directly, tell him he will need to contact your lawyer. You can remind him of your lawyer's telephone number. But otherwise you cannot comment. The parties themselves can, depending on the rules in your state, communicate with each other. This is usually not advisable, but not necessarily prohibited except right before trial. If the other party himself makes unwanted contact with you, tell your attorney what is happening. Your attorney can write to the opposing attorney demanding his client stop contacting you.

Because your initial reaction to the demand letter will likely be emotional, you should not respond to it yourself. Instead, consult a good civil defense attorney as soon as you receive the letter. You may also be shocked and fearful when you read the attorney's deadline for responding and the amount of damages he is claiming. Remember that plaintiff lawyers always exaggerate their damage amounts. The goal of the demand letter is to scare you into paying the amount or, secondarily, negotiating down to the "real" amount. The attorney's version of the facts will be skewed. Thus you may feel a desire to dash off a letter setting him straight. This is inadvisable. Consult an attorney instead. Demand letters are settlement negotiations, and as such, are inadmissible as evidence. But this does not mean you should be loose-lipped and not hire a lawyer. A settled case is final and precludes the plaintiff from filing the suit, and often the defendant from counter-suing.

Otherwise, civil cases have the following nine stages:

1. The complaint

Filing the complaint starts the civil action. The complaint states the grounds for the court‘s jurisdiction and describes the plaintiff's claim and relief sought. The complaint must be "served" on the defendant, either by hand-delivery by a court-appointed process server, certified mail, or leaving the complaint at the defendant's home or place of business. Once the complaint is served, the defendant has a limited time, usually thirty to forty-five days, to file her answer.

2. Defendant's answer/motion to dismiss

The answer is the defendant's response wherein you admit or deny the allegations in the complaint. You may also plead "affirmative defenses." Affirmative defenses are new facts or arguments the defendant alleges that would defeat the plaintiff's claim even if the facts in the complaint were true. Your attorney can tell you what affirmative defenses you have available. You may also include a counter-claim. A counter-claim alleges that plaintiff caused defendant injury and thus should pay for defendant‘s damages.

Your answer may also include initial motions attempting to defeat plaintiff's complaint automatically. These commonly include a "plea to the jurisdiction," "motion to dismiss," and "motion to clarify." A plea to the jurisdiction argues that the plaintiff has sued in the wrong court. For example, that the amount in controversy falls below the amount required for filing suit in that court.

A motion to dismiss essentially alleges that the plaintiff has not stated a claim the law officially recognizes. For example, a state may allow claims for intentional infliction of emotional distress, but disallow claims for negligent (unintentional) infliction of emotional distress. The motion to dismiss would argue that the plaintiff, by law, couldn't prevail.

A motion to clarify alleges that the plaintiff's complaint is not specific enough or is unclear. The motion asks the court to order the plaintiff to re-plead or explain his complaint more specifically, and if he does not do so, to dismiss the case.

If you are served with a complaint, regardless of the type of suit, you must find a lawyer immediately to file an answer--if you do not already have a lawyer. There is always a time limit for filing the answer. Failure to file the answer without just cause can result in an automatic "default" judgment for the plaintiff. It is very difficult to overcome a default judgment if the plaintiff validly served the defendant. Find a lawyer immediately to get your answer filed. After your attorney files the answer, the parties engage in discovery.

3. Discovery

Discovery is the process by which the parties ask each other to produce evidence. It is done formally, but outside of court. The purpose is to learn new facts before trial. Discovery is vital because it avoids surprise at trial. Discovery documents are not filed with the court except to resolve controversies, though documents may be used as evidence. The law recognizes six discovery methods:

(1) Interrogatories

Interrogatories are written questions sent by one party to another party. Interrogatories cannot be sent to witnesses. The receiving party must answer the questions in writing and under oath. The responding party may object to one or more of the questions. Your attorney should assist you in answering them. Interrogatory answers are not normally filed with the court unless some controversy requiring court intervention occurs or a party wants to use an answer to refute the other party's testimony in court. An interrogatory might read: "List the names and locations of all schools you have attended after high school, including but not limited to, all schools of midwifery; and state the dates of attendance and graduation for each school and degree received."

(2) Requests for production of documents

Requests for production are written statements demanding the other party deliver relevant documents to her. Any documents produced can be evidence. Absent valid objection, all documents asked for must be produced. Any documents not produced are excluded as evidence. Parties may request different types of documents be produced in one request if the documents belong to one specific category. For example, a request for production can ask for all licenses, certificates, and other documents showing that the responder is a licensed midwife.

Formal requests for production can be served only on parties. But parties can force witnesses to produce documents via subpoena. This is done with a subpoena duces tecum. This type of subpoena demands that the witness bring the requested documents to a scheduled deposition or trial. A request for production might read: "Produce copies of all certificates, licenses, degrees, diplomas, or other documents issued by a school, government, or administrative agency qualifying you to practice midwifery, nursing, medicine, or any other health related field or occupation."

(3) Request for admissions

Request for admissions are specific, written statements one party serves on another party who must then admit or deny each statement under oath. Request for admissions are served only on parties, not witnesses. In most jurisdictions, if a party does not deny a requested admission, it is deemed admitted. Requests for admission are used to confirm the genuineness of documents, or establish what facts are contested and thus must be "tried." A request for admission might read: "Admit or deny that the Maryland Board of Health Occupations issued you a cease and desist letter in 2003."

(4) Depositions

Depositions are live testimony done out of court and recorded for later use in court or simply for learning new facts. Subject to specific rules, any party or witness may be deposed. Depositions let the parties confront each other and learn of new facts and witnesses quickly. They also help show how a party or witness will testify in court and pre-establish a person's testimony so he cannot change it at trial. Depositions are usually the most efficient--but most expensive--discovery method. Depositions can also be the most abusive form of discovery because they are directly confrontational and no judge is present. Also, though an attorney may object to a question in deposition, the deponent must answer the question despite the objection. Exceptions are made only for questions asking for privileged information or that are overly intrusive, argumentative, harassing, or otherwise grossly improper.

The party demanding the deposition decides the location for it. Remember, deposition testimony is considered live, binding testimony, under oath. See "Deposition tips" for advice on being a deponent.

(5) Entry upon land

This is an uncommon form of discovery, generally used only in cases where a party needs to examine some land or property to see or obtain evidence or where the land or its conditions are evidence itself.

(6) Psychological or medical examination

If one party is claiming physical or psychological damages, or physical or mental condition is otherwise a critical fact in determining liability and damages, then either party can make a motion to have the other party undergo a medical or psychological exam. The doctor or psychologist evaluates the condition's severity, cause, and prognosis. The court must usually order the exam after determining good cause exists for it. The movant usually suggests the doctor. The opposing party can object to using that particular doctor.

- Preventing or enforcing discovery

Ethics and fairness in discovery is enforced by two general types of motions filed with court, motions for protective order and motions to compel.

Parties seek protective orders when they feel the discovery sought is improper, unethical, overly intrusive, harassing, or otherwise wrong. Protective orders seek to restrain the other party from engaging in the discovery tactic or to limit the discovery sought. For example, because there is no precise time limit for depositions, a deponent may decide to ask the judge for a protective order to stop or limit a deposition that is going on too long and is being used simply to wear the deponent down or run up her fees. Witnesses may also file protective orders and motions to quash subpoenas to avoid or defeat improper discovery requests. For example, if one party issues a subpoena duces tecum asking for the outtakes from a local news interview the other party partook in, the news station might file a motion to quash the subpoena and a motion for protective order asking the court to restrain the requesting party from obtaining the privileged film clips.

Parties file motions to compel when opposing parties refuse to comply with discovery requests. For example, a party may file a motion to compel when the other party refuses to answer a valid interrogatory or deposition question.

4. Pre-trial conference

The pre-trial conference is a meeting between the parties, often in front of the judge, to establish how to proceed with the pre-trial aspects of the case. After the pre-trial conference, the judge will usually issue an order declaring the rules for the remaining pre-trial procedure.

5. Motions for summary judgment

A motion for summary judgment seeks to have the court decide the case without trial. The motion asserts that no genuine issue of fact exists and that the party making the motion ("movant") should prevail by law. Remember, trials are held to decide facts. But if all important facts are agreed upon, or obvious from the discovery, then no need for trial exists and the judge can rule based on the law. Courts frequently deny summary judgment motions because responding parties need only raise a material, contested fact issue to defeat the motion.

6. Jury selection

Trials will be by judge unless a jury trial is requested. Jury selection takes place right before trial.

The first stage is interviewing the prospective jurors, called "voir dire". Voir dire consists of written and oral questions posed to the prospective jurors to determine who might be biased or unqualified. Most courts let parties question prospective jurors individually and as a group. The goal is to determine which jurors the attorneys should challenge (seek to eliminate). Attorneys can challenge jurors for "cause" or for no particular reason ("peremptive challenge"). Challenge for cause means the attorney wants the juror eliminated for some fundamental legal reason. For example, a juror may be related to one of the parties or attorneys. The court must approve the challenge. Parties are unlimited in how many cause challenges they may bring. But the court must find and rule that the juror is disqualified.

Peremptive challenges require no shown cause. The parties can eliminate jurors at their choice for any reason except race, ethnicity, or gender. The catch is that parties are limited in how many peremptive challenges they get. A typical number is three per party.

States vary on the number of jurors used in civil cases. The number ranges typically from six to twelve. After voir dire is complete, and the requisite number of individuals is selected, the jury is sworn in. The trial begins.

7. Trial

Civil trials, in the courtroom sense, consist of the following ten stages:

(1) Opening statements

Immediately after the jury is sworn in, the attorneys make their opening statements. They tell the jury what they are suing for, what they would like the jury to find, and what they will prove. The plaintiff usually goes first. The parties can say what the evidence will show, but cannot describe the evidence in detail. During trial, witnesses are not usually allowed in the courtroom other than to testify.

(2) Plaintiff's case

(3) Defendant's case

The procedure for the plaintiff and defendant presenting their cases is essentially the same as that for the prosecution and defendant in criminal cases. The plaintiff presents his case first. Unlike criminal cases, parties in civil cases must testify if called. Neither parties nor witness in civil cases have a Fifth Amendment right not to testify unless their answer to a particular question could likely give evidence of their own crime. Civil cases do not decide crimes. Thus, revealing one's own liability is not incrimination. States avoid Fifth Amendment problems where a defendant is to be tried both criminally and civilly by trying the criminal case before the civil case.

(4) Motion for directed verdict

The directed verdict motion argues that, because all important facts are known, the jury has nothing to decide. The evidence is so overwhelming or insufficient that the verdict is a matter of law, which the court should direct. Courts seldom grant directed verdict motions.

(5) Closing arguments

After all of the evidence is presented, the lawyers summarize their cases by arguing what effect the evidence had and what the evidence showed. The plaintiff usually goes first.

(6) Jury instructions

Jury instructions are instructions the court gives the jurors to direct them in deliberating and reaching their verdict. The instructions are tailored to the elements of the claim. Like criminal offenses, civil claims have elements that must be proved. For example, the elements of negligence are the (1) breach of a (2) duty (3) proximately causing (4) damages. After the court instructs the jury, the jurors retire to the jury room to deliberate.

(7) Jury deliberations

Unlike in criminal cases, civil juries need not reach a unanimous verdict, but only a significant majority vote one way or the other. States vary as to how much of a majority vote is required to reach a verdict for the plaintiff. A typical ratio for a verdict for the plaintiff might be ten of twelve or six of eight. A lesser number finding for the plaintiff means the jury finds for the defendant. In torts, juries generally decide whether liability exists and, if so, decide separately what the damages amount is.

(8) Motion for judgment as a matter of law

The motion for judgment as a matter of law (also called judgment notwithstanding the verdict) comes after the jury returns their verdict. The movant asks the court to disregard the verdict because it is obviously wrong. If the court grants the "JMOL," then the judge will make the "proper" verdict. Courts seldom grant motions for JMOL.

(9) Closing arguments

After all of the evidence is heard, the lawyers summarize their cases to the jury, explain what the evidence showed, and ask the jury for a verdict. There is usually no strict time limit.

(10) Motion for new trial

The losing party in a civil case still has a remedy in the trial court before needing to appeal. That remedy is the motion for new trial. The motion asks the court to grant the losing party a new trial because a fatal error occurred or new evidence was discovered. Making a motion for new trial may be necessary to preserve a lack of evidence argument on appeal. The motion for new trial may also extend the deadline for filing an appeal. If the court denies the new trial motion, the losing party's remedy is to appeal.

Stages of Proceeding

An adverse administrative proceeding usually involves a decision about disciplinary measures and the status of a member's license. The case begins when someone files a complaint with the administrative agency. A complaint can come from the public, a member of the profession being offended (e.g. doctors, nurses, midwives), or by the agency itself. An agency can investigate the allegations of the complaint. If it decides to proceed with disciplinary or other, notice is given to the licensee. Much like a civil court case, the administrative proceeding can proceed through discovery, pre-hearing conference, and hearing.

The hearing is presided over by an administrative law judge ("ALJ"), sometimes called "hearing officer" or "referee." The hearing follows the agency's specific rules of evidence and procedure where those rules do not default to the county court's rules. Typically, after the hearing, the ALJ issues a "recommended" decision to a superior administrative council. That council either accepts, reverses, or modifies the recommended decision, or remands the case to another ALJ for a new hearing. The superior council is the final "judge" administratively.

A party unhappy with the Council's final decision can appeal to the county civil court. This is the one instance where a first-level county civil court acts as an appellate court. Courts defer strongly to administrative agency determinations of fact and usually uphold the agency's decision if some competent evidence supports it. The party losing the appeal in the county civil court can appeal to the state appellate court. Losing there, the party can seek review in the state supreme court. From there, one can petition the U.S. Supreme Court.

An administration agency need not bring the case to the administrative tribunal. It can instead pursue criminal charges or orders in the county courts. This usually applies where the alleged offender is not licensed. Here is where criminal, civil, and administrative law interact, and where administrative agencies can select different remedies.

Interaction between criminal, civil, and administrative law; and the election of remedies

Administrative agencies have three general options to pursue in enforcing their regulations against non-licensed offenders: (1) issuing a letter to the alleged offender to "cease and desist" their activity, (2) file a complaint in the county civil court asking the court to issue the offender an injunction, or (3) file a criminal complaint with the prosecutor who then brings a formal criminal charge against the alleged offender in the county criminal court.

If the state has a licensing agency for midwives, and an unlicensed person is practicing midwifery, the licensing agency can pursue all of the above remedies. If the person possesses a midwifery license, then the licensing agency can also seek suspension or revocation of the midwife's license. For example, a board might suspend the license of a nurse who attends a homebirth where that action exceeded the scope of the nursing license. That would require an administrative hearing with the administrative procedure described previously.